If you have some

free time and a few, or closer to 225,000 give or take, barley grains lying

around you can give this little medieval math problem a whirl. Since they didn’t have trains at the

beginning of the ninth century or Newton’s laws of

motion, no medieval math whiz was going to be faced with the problem of when and where do the two trains meet. On the scale of medieval math, the

question of how many grains of barley go into a mile is still pretty

simple stuff, but our author seems fairly pleased with himself nonetheless.

|

| St. Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Cod. Sang. 751: A compendium of 39 medical texts (http://www.e-codices.unifr.ch/en/list/one/csg/0751). |

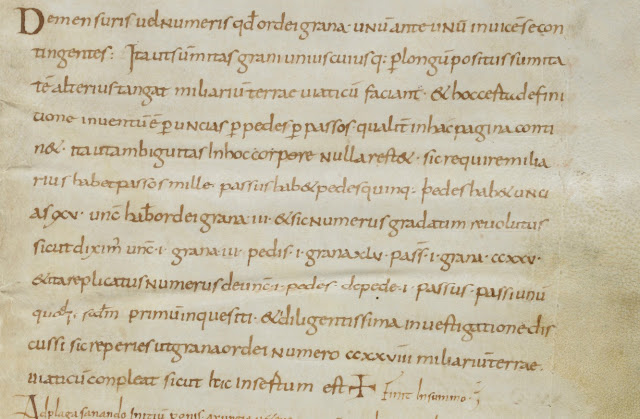

De mensuris vel numeris quod ordei grana unum ante unum in vicem se contingentes, ita ut summitas grani uniuscuiusque per longum positus sumitatem alterius tangat miliarium terrae viaticum faciant et hoc certa definitione inventum est per uncias per pedes per passos. Qualiter in hac pagina continet ita ut ambiguttas in hoc corpore nulla restet sic require[t] miliarius habet passos mille, passus habet pedes quinque, pedes habet uncias xv, uncia habet ordei grana iii. Et sic numerus gradatim revolutur sicut diximus unica i, grana iii, pedis i grana xlv, passus i grana ccxxv et ita replicatus numerus de uncia i pedes de pede i passus, passi unum quodque secundum primum inquesiti. Et diligentissima investigatione discussi sic reperies ut grana ordei numero ccxxv milliariae miliarium terrae viaticum conplea[n]t sicut hic insertum est.

About the measures or the numbers that grains of barley touching one to the next in turn, so that the extreme end of each and every grain through the length of the arrangement touches the end of another, make a journey of one land mile and this was found by sure definition through the inch, the foot, the yard. How it hangs together on this page so that no ambiguity may remain in this body (of work), thus requires that the mile have one thousand yards, one yard have 5 feet, a foot have 15 inches, one inch have 3 grains. And in this way, the number rolled back step by step just as I said, one inch is 3 grains, one foot is 45 grains, one yard is 225 grains and thus the number is repeated over and over, from one inch, feet, from one foot, yards and yards sought each according to the first. With the most careful research I pleaded my case, thus you will find that the grains of barley in the number of 228000 fill up a journey of one land mile just as it was set out here.

This text is found on page 39 of the St. Gall Stiftsbibliothek Codex Sangellensis 751.

This manuscript is a medical miscellany produced somewhere in Northern

Italy in the first quarter of the ninth century.[1]

It can be readily viewed at the e-codices website, along with the other

manuscripts of their extensive, beautifully digitized collection. The transcription and translation is my own.

The use of barley as the

base of a measurement system has extensive roots. References to its use to measure weight are

found on clay tablets from Babylon.[2] The use of 3 barleycorns to denote an inch was

recorded in Scotland in 1150 AD.[3] But why did this scribe choose to place this

little gem where he did? The text

follows directly an entry about the weights, measures and the symbols used to

denote them. This would be a very

important piece of information for anyone trying to make the medical recipes

which are found throughout this manuscript.

Some of the recipes include ingredients like opium, henbane and mandrake,

all of which can be dangerous in high doses.[4] The barley grain text very clearly

demonstrates how to relate one measure to another mathematically, in a

step-wise fashion. This method could be

used for any of the other weights described, providing a useful template for

anyone else faced with calculating the number of any given measure contained in

another. That the explanation is a

little self-congratulatory makes it just that much more memorable.

|

| Barley With and Without Husks By Sanjay Acharya (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons |

Whether this was the scribe’s own work, I have been unable to find a similar text elsewhere, or whether it was copied from somewhere else, it gives us some insight into the measurements used in ninth-century Europe and gives an example of a medieval approach to a mathematical calculation. Also, now you have one thing to do with thousands of barley grains, you’re welcome!

[1] Augusto. Beccaria, I codici di medicina del periodo

presalernitano (secoli IX, X e XI) (Roma: Edizioni di Storia e letteratura,

1956), 372–81. For a

fairly complete description of the contents.

See also Guy Sabbah, Klaus-Dietrich Fischer, and Pierre-Paul

Corsetti, eds., Bibliographie Des Textes Médicaux Latins: Antiquité et Haut

Moyen âge, Mémoires / Centre Jean-Palerne 6 (Saint-Etienne: Publications de

l’Université de Saint-Etienne, 1987).

[2] Jöran

Friberg, A Remarkable Collection of Babylonian Mathematical Texts:

Manuscripts in the Schøyen Collection: Cuneiform Texts I (Springer Science

& Business Media, 2007), 112.

[3] Ronald

E. Zupko, British Weights & Measures: A History Form Antiquity to the

Seventeenth Century (University of Wisconsin Press, 1977), 199.

[4] Ben-Erik

Van Wyk and Michael Wink, Medicinal Plants of the World: An Illustrated

Scientific Guide to Important Medicinal Plants and Their Uses, 1st ed

(Portland: Timber Press, 2004), 174, 225, 416. All three of these plants

contain substances now used in science-based medicine.