|

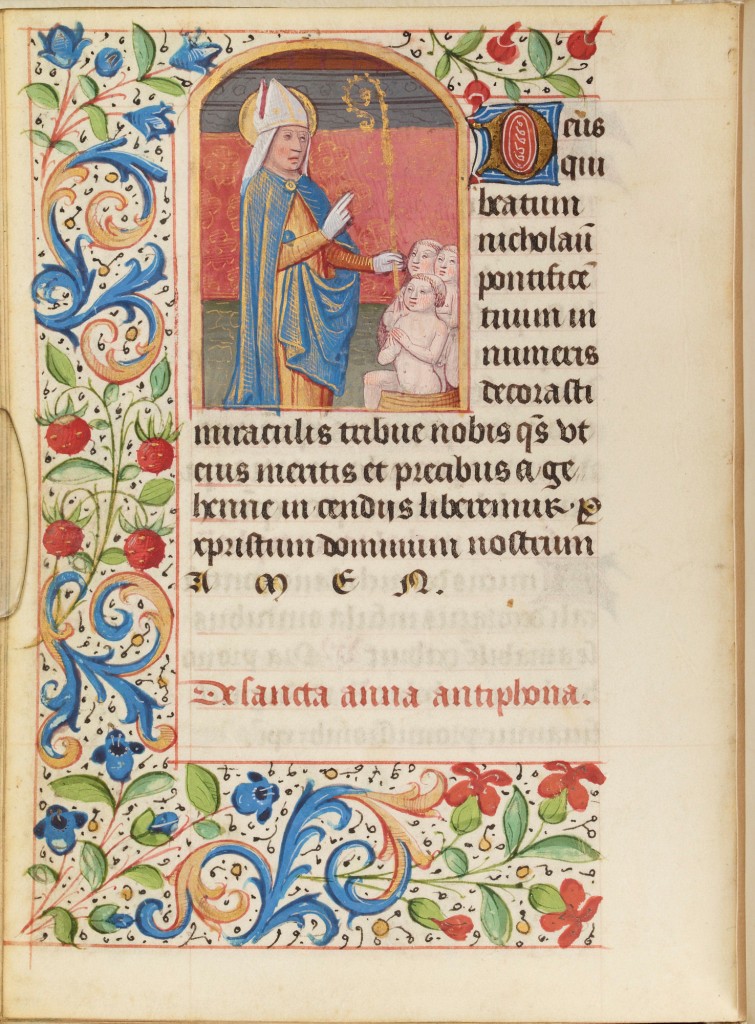

St Nicholas depicted in a medieval Book

of Hours, LUL MS.F.2.8, from University

of Liverpool Library

|

I don't want to start a conspiracy theory (or maybe I

do) but I was having a conversation with my mom about Charlemagne. My mother grew up in Germany and learned

about Karl der Große,

and apparently his red mustache in grade school. "RED?" I gasped, "How would

they know what colour his hair was?"[1] This after reading much about the

Carolingians and their correctio and emendatio as part of my

fields preparation. I don't want

to think about how things might have gone had that question come up. So, while still on the phone I leafed through

to Einhard's Vita Karoli and found a description. A description so evocative, that as I read it

aloud to my poor, captive-audience mother I burst out, "It's Santa

Claus!"

“His body was large and

strong; his stature tall but not ungainly, for the measure of his height was

seven times the length of his own feet. The top of his head was round; his eyes

were very large and piercing. His nose was rather larger than is usual; he had

beautiful white hair; and his expression was brisk and cheerful; so that,

whether sitting or standing, his appearance was dignified and impressive.

Although his neck was rather thick and short and he was somewhat corpulent this

was not noticed owing to the good proportions of the rest of his body. His step

was firm and the whole carriage of his body manly; his voice was clear, but

hardly so strong as you would have expected.”

Santa

Clausy, right? Well compare this to the

description in the famous poem, A Visit from St. Nicholas, by Clement

Clarke Moore, which is better known by its opening line, ‘'Twas the night

before Christmas'. Clement writing for

his children gave a very careful description of Santa Claus,

His eyes--how they twinkled! his dimples,

how merry!

His cheeks were like roses, his nose like

a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up like a

bow,

And the beard on his chin was as white as

the snow;

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his

teeth,

And the smoke, it encircled his head like

a wreath;

He had a broad face and a little round

belly

That shook when he laughed, like a bowl

full of jelly.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old

elf...

On closer examination, Santa is portrayed as a happy,

genial fellow, and no one alive or dead would refer to Charlemagne as an 'elf'

but look at some of the comparisons. Like Santa Claus, in the English version

of the Vita, Charlemagne's hair is described as white, however,

in Latin Einhard used the phrase 'canitie pulchra' beautiful grey or

greyish white hair. I think perhaps

there may be some ageism on the part of the English translators who cannot

imagine beautiful hair being any shade of grey and so translate it out to

white. Maybe Einhard would have

agreed.

Both writers spend time on small details highlighting

features that I bet most people, or just me, hardly pay attention to. Charlemagne's eyes are very large and

piercing, while Santa's are

|

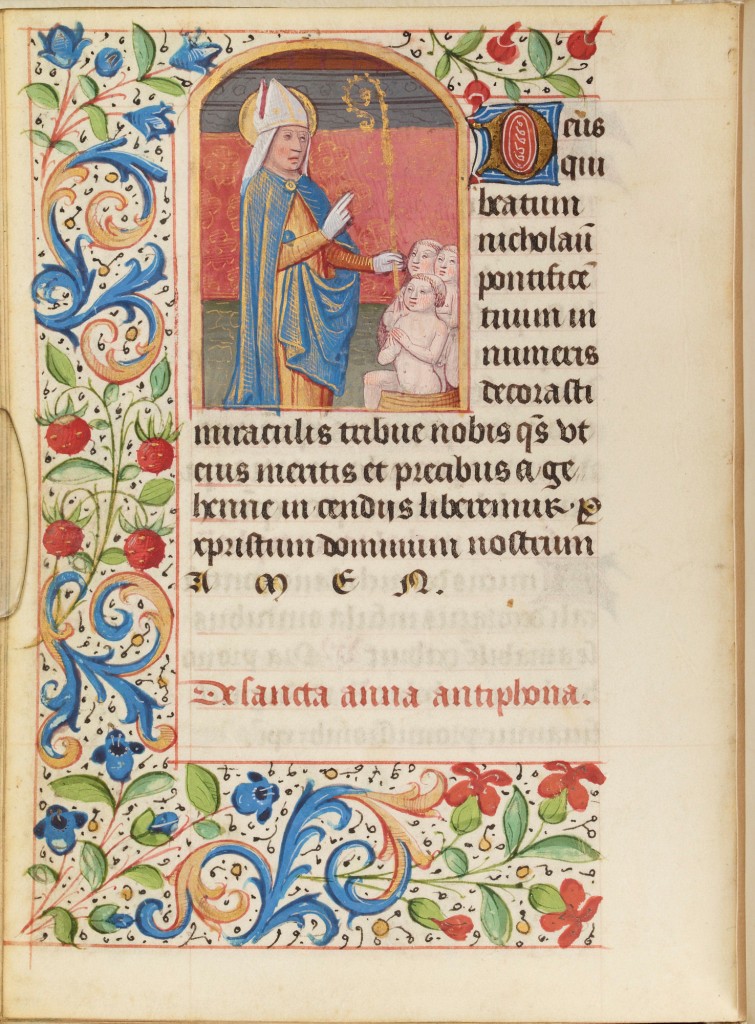

Coronation of Charlemagne, Grandes Chroniques

de France. Bibliothèque nationale de

France, Français 2813, fol. 85v. 14th Century

|

twinkling.

Both descriptions imply lively intelligence and the ability to quickly

assess any situation. Santa must know

whether you are naughty or nice. Santa

is a 'right jolly old elf' while Charlemagne was 'brisk and cheerful'. Both had noses worth noting, Charlemagne's

large and Santa's like a cherry, but neither were mundane run-of-the-mill

noses. Both are a tad corpulent, though only Santa's belly shakes like

jelly. Oh, the rhymes! Both are

described in physical terms which create the sense of good natured, physically

and mentally capable older men who enjoy a good chuckle, the older fun uncle

who tells great stories at Christmas, not that other one, you know, who drinks

too much and wants to talk about politics. Certainly, neither description is frightening

or intimidating.

Therefore, Santa is Charlemagne and Charlemagne is

Santa. You have never seen them in the

same room, have you? Charlemagne, sadly,

is nowhere reported to ascend or descend chimneys. That would have clinched it.

So why might these two characters, and I use the term

purposefully, have similar appearances, or more precisely appearances crafted

in this specific way? The reason that I

call both men 'characters' is not to say that Charlemagne is not a real person,

of course he was. This description of

him though was written at some time after he died. Einhard (c. 770 - March 14, 840) the

biographer who penned the Vita Karoli, had served in Charlemagne's court

and by his own admission owed the king much.[4] Since the life describes Charlemagne's death,

it had to be written after 814, but exactly how long after is not known. Also not known is how accurate Einhard could have

been, had he wanted to be accurate? What is known is Einhard's very Carolingian

habit of using other texts as models for his work. Models which lent phrases and an

organizational structure to the Vita. One text in particular offered Einhard a a way

of organizing the biography and also a way to frame Charlemagne so that his

biography could stand as a shining example to his son, Louis the Pious (778-

June 20, 840).[5] This text was the De vita Caesarum, About

the lives of the Caesars, by Suetonius, written sometime in the late first

to second centuries. Life under Louis

the Pious was turbulent, just as the period in which Suetonius had lived. Both writers were offering their readers

examples of proper, peaceful rule.

Minjie Su makes this argument when they compare the parts of Suetonius

Einhard used and what he did not. The

white hair and the perfect proportions ascribed to Charlemagne are lifted

almost directly from De vita Caesarum.

Equally important, Einhard left out many violent episodes from the Royal

Frankish Annals. Perhaps Einhard hoped

that highlighting Charlemagne's less violent methods might help to guide

Louis's choices.[6] So one can say that Einhard took the best

parts of Charlemagne and reflected them in his biography, carefully crafting

the greatness in Charles's persona and person.

Now Santa Claus, on the other hand, is a fictional

character; sorry Virginia. And so, Santa

as the focus of scholarly attention might surprise you. While some of that attention serves as a foil

to pursue other avenues of intellectual debate, as when Justin Barrett

submitted the jolly old elf to the test for godhood; he fails. Likewise, the computational dilemma of

getting Santa ready to go on Christmas Eve is known as the Santa Claus Problem[7],

which was solved by Mordechai Ben-Ari in 1998.

These studies underline how deeply entrenched Santa Claus is in North

American culture, and to varying degrees in Europe.

Santa Claus has become a secular icon, but he did not

start out that way. In 1809, Washington

Irving removed St. Nicholas's mitre and bishop's clothes and gave him 'a

low-brimmed hat, a huge pair of Flemish trunk hose, and a pipe that reached to

the end of the bowsprit.' Washington was

writing a tongue in cheek history of New York City under the pseudonym of

Dietrich Knickerbocker.[8] The Knickerbocker came from a term used to

describe New Yorkers of Dutch origins.

Maybe a not so nice term? And

viola! St. Nicholas, the fourth century saint from Myra, was firmly on the path

to Santa Claus. But this was not the first step in the saint's progression from

religious intermediary to shopping mall fixture. Jeremy Seal traces the personified saint

through this journey by taking his own.

When discussing the mid-nineteenth-century success of Santa, he

suggests,

"Santa had proved a enormous

success among Americans; it was striking how closely he had mirrored the

achievements of St. Nicholas though their worlds lay centuries apart. The truth was the Harper's [Bazaar]

and hagiographies, parades and saints' plays, Coke ads and frescoes served the

same purpose in those different worlds.

Santa and saint had always been interested in the same thing, which was

to spread their names among the widest audiences. It was true that they had come to be

associated with different values, but they still shared an essential notion of

generosity that was the core of their appeal to children and their parents alike. [9]"

Coca-cola just spurred things along when they claimed

the now unambiguously named Santa Claus; the name had taken awhile to settle. The image that was Santa in the Coke ads may

have reflected a collective memory of sorts, but the Coca Cola image of Santa was a formidable force in the development of a single, accepted vision of what the term Santa Claus represented by way of a physical description.[10] So, despite our having no frame of reference

for what Clement Clarke Moore was describing as Santa Claus we all fill in the

red suit wearing overweight white haired man we have come to know and instantly

recognize. So how is Santa Claus Charlemagne?

I would refer again to Seal's summation that

generosity is as the heart of who Santa is.

I would add that generosity comes from a generous spirit, which cannot

grow so easily in difficult times. Santa

and Charlemagne are both portrayed as men who aged reasonably well. Einhard does describe Charlemagne's health

problems in the year before his death, but he was already the cheerful,

slightly paunchy, white-haired man by then.

If we think back to the turbulence of Einhard's days when he was writing

the Vita and think that the text was encouraging behaviour that would

lead to peace, we realize that that is the message of the image. Charlemagne was at peace. Santa, St. Nicholas, can be generous because

he is at peace. And even if you have no

religion, you have to recognize that peace is part of the central message of

Christmas, after all the cards say, "Peace on Earth!" An old man grown fat in peaceful times can be

generous. Perhaps that is why Santa is

so successful, children love the toys he brings, and parents want to grow old

in peace and well being, able to shower future generations with

generosity. It's what Einhard wanted for himself and his kingdom and what he crafted in his image of Charlemagne.

Therefore, Charlemagne is Santa Claus. I wish you all Peace and Joy this holiday

season!

[1] Germanic

tribes are noted to have coloured their hair red, but in pre-Carolingian times.

The Carolingians represented a turn away from hair as a symbol of power. For

more on the hair habits of the barbarians, see: Paul Edward Dutton, Charlemagne’s

Mustache: And Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age, 1st ed, The New Middle

Ages (New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 9.

[4] Notker

The Stammerer and David Ganz, Two Lives of Charlemagne., 2008, 17; For

the most recent scholarship on Charlemagne, see: Janet L Nelson, King and

Emperor: A New Life of Charlemagne (London: Allen Lane, 2019).

[5] Su (2019), Nicoll (1975), Kempshall (199Minjie

Su, “Profile of An Emperor: Reading Vita Karoli Magni in Light of Its Sources

and the Socio-Political Context of Its Composition,” Ceræ : An Australasian

Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies 5, no. 1 (April 17, 2019),

http://openjournals.arts.uwa.edu.au/index.php/cerae/article/view/135; W. S. M.

Nicoll, “Some Passages in Einhard’s ‘Vita Karoli’ in Relation to Suetonius,” Medium

Aevum; Oxford 44 (January 1, 1975): 117–121; Matthew S. Kempshall, “Some

Ciceronian Models for Einhard’s Life of Charlemagne,” Viator; Berkeley,

Calif. 26 (January 1, 1995): 11–37.

[6] For

a less negative take on the rule of Louis the Pious see: Rutger Kramer, Rethinking

Authority in the Carolingian Empire: Ideals and Expectations during the Reign

of Louis the Pious (813-828), The Early Medieval North Atlantic 6

(Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2019).

[7] Mordechai

Ben‐Ari, “How to Solve the Santa Claus Problem,” Concurrency: Practice and

Experience 10, no. 6 (1998): 485–96,

https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1096-9128(199805)10:6<485::AID-CPE329>3.0.CO;2-2.

[8] Jeremy Seal, Santa: A Life (London: Picador,

2005), 192.

[10] Cara

Okleshen, Stacey Menzel Baker, and Robert Mittelstaedt, “Santa Claus Does More

than Deliver Toys: Advertising’s Commercialization of the Collective Memory of

Americans,” Consumption Markets & Culture 4, no. 3 (January 1,

2000): 207–40, https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2000.9670357.